Baltimore Resident Captures City’s ‘Beautiful Chaos,’ Archiving Graffiti, Signs, and Stickers

Patrick Swickard, a software developer and engineer who relocated from Milwaukee to Mount Vernon in 2012, quickly discovered Baltimore’s vibrant graffiti scene, particularly in the aptly-named Graffiti Alley within Station North. However, it was the less remarkable but intriguing graffiti tags and graphic posters spread across Baltimore’s sidewalks, walls, and utility poles that truly captured his attention.

Seeing the beauty in these seemingly mundane expressions, Swickard decided to bring them to the forefront by photographing them. Over a period of more than six years, he amassed around 30,000 photos, focusing on the impromptu markings and flyers left to the mercy of the elements. To preserve this ephemeral form of communication, he diligently uploaded his collection to Flickr, created his own website, and even developed a 50-volume series of PDF books using his coding skills.

Of course, capturing graffiti involves documenting something that is often illegal, but Swickard saw it as an overwhelming part of Baltimore’s streetscape. Despite being in “The City That Reads,” as the slogan goes, Swickard humorously points out that he spends much of his time wandering around, reading the graffiti.

Swickard’s commitment to exploring the city on foot is rooted in his desire to remain active, considering the sedentary nature of his work as a software developer. Having relinquished his car upon moving to Mount Vernon, he relies on walking as his primary mode of transportation. Armed with a pocket-sized Sony camera, he started taking casual photos during his Baltimore outings in 2013. Sometimes, he even set out specifically to document particular posters, tags, and markings, such as spray-painted messages and stickers adorning street signs.

Despite not being a professional photographer, Patrick Swickard had experience working with metadata, the information attached to photos that provides details about their origin, location, and content. His job at a commercial stock and art photography company in Madison, Wisconsin, made him ponder the relationship between words and visuals.

Sara Cotton, who hired Swickard, recalled cautioning him about the transformative effect of working with metadata. As he delved into his own project, Swickard began seeing scenes as if they were accompanied by comic strip speech bubbles or descriptive captions, thanks to the keywords associated with the images.

Throughout his project, Swickard shared his Baltimore discoveries with Cotton through various digital platforms. She recognized the value of photo archives as a wealth of knowledge, and in Swickard’s case, his photos were telling “the story of living in Baltimore.”

Some of Swickard’s photographs were even included in an archive project documenting the aftermath of Freddie Gray’s death in Baltimore. Other albums on Flickr showcased the rise of e-scooters from companies like Bird.

Swickard’s photos typically avoid depicting people, but when he encountered someone actively tagging with spray paint, he assured them that he had no intention of reporting their actions. He was concerned about the potential misinterpretation of his images and didn’t want them to be used to portray Baltimore negatively.

In April, Baltimore’s Mayor launched a graffiti cleanup initiative, reflecting the city’s efforts to address the issue. However, Swickard noticed what he considered a “weird logic” behind where people chose to graffiti, often avoiding certain areas to respect homeowners.

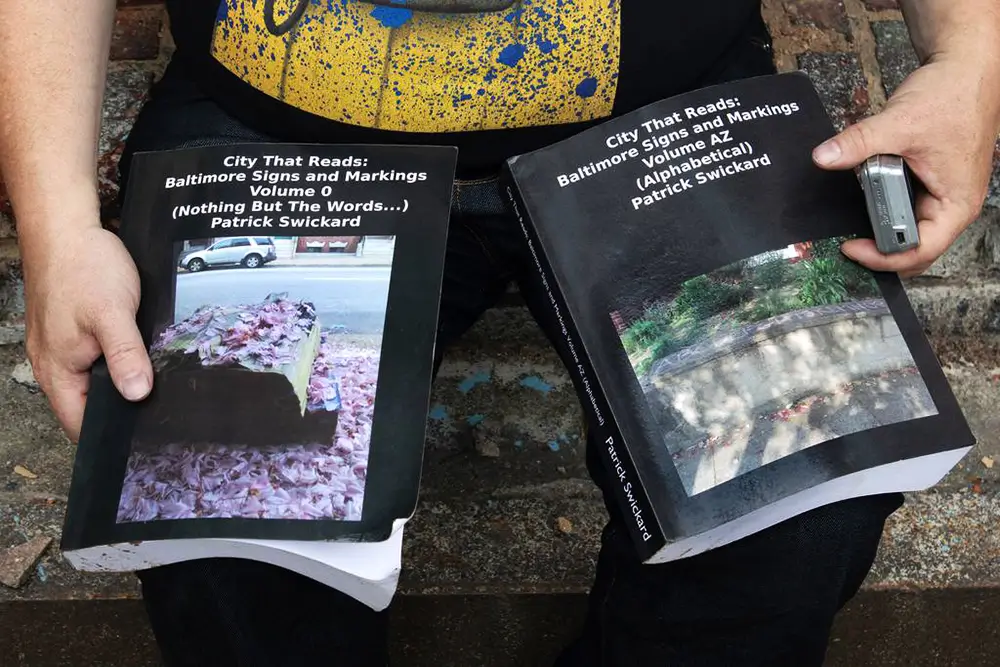

Swickard’s photography project slowed down around 2019 due to an injury and burnout from his intense dedication. Nonetheless, he continued by writing code to create PDF files for his series of “zines” or photo books. These zines, comprising 150 to 200 pages, contained two to four photos with captions per page, showcasing the graffiti he had documented.

Two additional index volumes, longer than the photo zines, contained all the captions chronologically in one and alphabetically in the other. Swickard printed some of the books via a self-publishing service and sold two volumes to someone who frequented a local bar.

As his work on the project unfolded, Swickard found appreciation and interest from others who were curious to see how Baltimore looked before their time in the city. Though he didn’t have plans for wide-scale book distribution, his photography book found a place on display in a local coffee shop.