Hip-Hop Gear That Changed the Game: Graffiti Edition

Analyzing the prevalent writing instruments and essential graffiti implements found in the toolkit of any 1980s artist—many of which were far from ordinary off-the-shelf items.

These were standard tools taken to the next level, utilizing expertise passed down through generations or acquired from the urban landscape.

To acquire comprehensive insights into the essential equipment for conducting genuine bombing runs in early 1980s New York, we turned to Adam McLeer, a rapper from Lordz of Brooklyn, a lifelong graffiti artist (he began tagging trains at the age of ten in 1981), the younger sibling of the renowned NYC artist Kaves, and now an innovator in the field of rug bombing.

Adam McLeer, formerly identified by the NYPD as the vigilante tagger “YR” and “ADM,” has an extensive background in the graffiti scene. Speaking of encounters with the law enforcement, let’s delve into that subject.

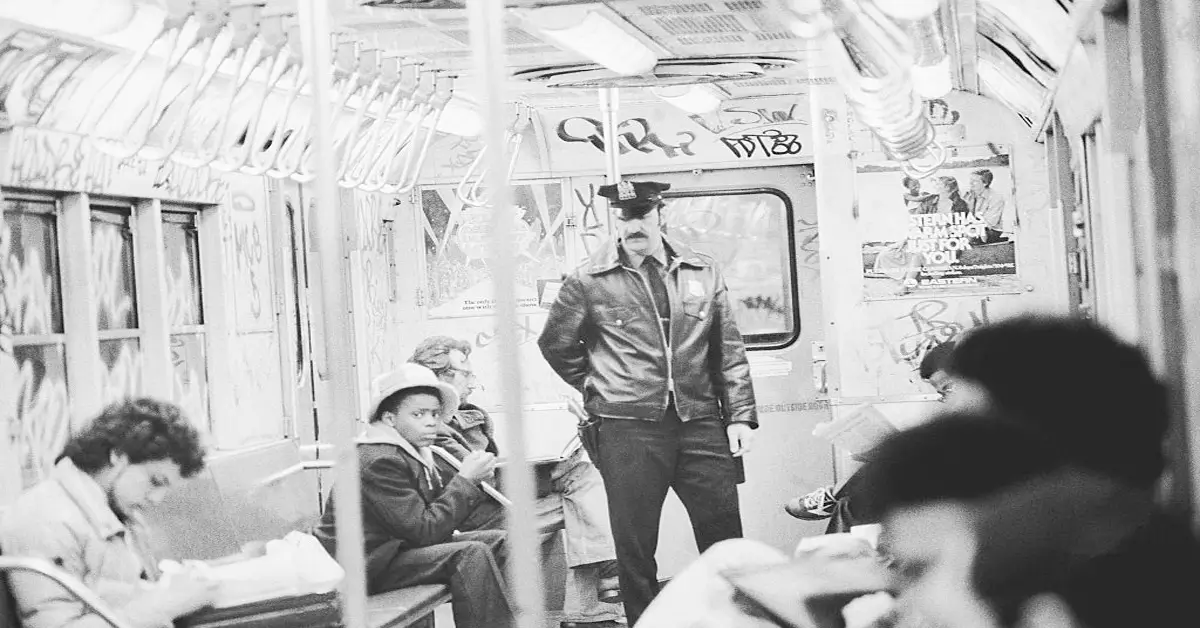

NYPD Vandal Squad

Legend has it that the first truly memorable New York graffiti emerged in the mid-1950s with “Bird Lives!” tags, paying tribute to the jazz legend Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker, who left us too soon.

These tags began to surface. As the 1970s dawned, graffiti, in the form we recognize today, made its initial, captivating appearance. Pioneering artists like TAKI 183 and Tracy 168 began leaving their marks on trains traversing the city.

Over the course of the 1970s, a dedicated graffiti-art movement took shape, with some regarding it as a valuable form of expression and others as a detrimental visual nuisance. By the end of the decade, graffiti had transformed into a significant criminal issue in New York City, extending from the Bronx and Washington Heights into all five boroughs, particularly Brooklyn. In 1980, the NYPD launched a specialized anti-graffiti task force known as the Vandal Squad.

“Since the inception of graffiti, the NYPD has consistently maintained a version of the Vandal Squad. There were transit cops for a brief period too, but they were phased out in the late 1980s or early 1990s.

However, the Vandal Squad, the graffiti writers were well aware of some of them, the most notorious ones. It was like, ‘Beware of Frank and Eddie; they’ll rough you up, handcuff you to a train, and bring you into the station the next morning.’

As a matter of fact, I believe they have a more extensive Vandal Squad now, and graffiti has become even more rampant. These kids are wreaking havoc on the trains, completely covering them from top to bottom. They’re going wild.

I know someone who works in the train yards, and he’s been sending me pictures of the trains as they roll in.”

TNT Bombers

In the early days, graffiti writers operating inside trains and stations certainly didn’t rely on the markers you’d find in our household pen and pencil drawers.

Forget about fine-point Sharpies, watery dry-erase markers, or child’s Crayolas; engaging in serious city-writing required substantial tools – the kind typically wielded by the big boys (or sometimes a whole set of them). These were custom-crafted ‘TNT Bomber’ markers, specially loaded with customized ink to get the job done.

The Ink

When you were a young graffiti artist mixing various ink colors together, you’d develop your own unique ink concoction—combining specific ounces of this color with that one to create your perfect shade.

And when paired with those TNT markers, it was like unleashing pure chaos. The TNT markers weren’t limited to just black ink; they offered an array of colors, including purples, greens, and reds.

Obtaining the necessary ink was a challenge. Stationery stores did carry it, but they were a rare find. And even when you did stumble upon a store selling the ink, they were exceptional quality inks.

But more often than not, we resorted to less conventional methods, like pilfering. There was this one particular ink, and if you could lay your hands on it, it had the remarkable ability to cover anything when used with a TNT marker, thanks to its robust eraser tip. The marker’s ink flow was nothing short of genius.

Pilot Bomber

The creation of these bombers was quite a craft. There was one particular method that involved using a Pilot marker, and you’d essentially rebuild the entire marker.

You’d remove the entire top and extract the eraser from inside, then pour in your ink. When mixing different inks, if you combined an opaque one with a regular ink, it could get a bit inconsistent, so we would drop a ball bearing in to help shake it up and blend it, similar to how you’d mix spray paint.

Lastly, you’d obtain a school eraser, one of those old chalk erasers, and fold a piece of it into the marker. Sometimes, I would even sew the tips to prevent ink from dripping out.

The only catch was that you couldn’t reseal the marker with its original cap after these modifications. So, some guys would dig out D batteries to create a metal tin cap that would fit over the new tip you’d inserted.

You’d wrap some electrical tape around the marker to connect it with the new cap, and it worked perfectly. We learned this trick from the older graffiti writers on the block, who were also known as hippies back in the day, when we were young and just starting out.

Deodorant Stick

Creating TNT markers took various forms, and one ingenious method involved using a deodorant bottle. With the addition of a felt eraser tip, the ink would reside inside the tip, unlike a typical jumbo marker bought at a hardware store.

If you filled that jumbo marker with ink and turned it over, it would just spill onto the floor. But with a felt-eraser tip, it would stay inside the marker, albeit completely soaked. It was truly remarkable.

Another unconventional option was the shoe polish applicator. These were those small plastic bottles with a screw-on tip used for applying shoe dye or cleaning shoes.

Graffiti writers like myself would empty out the shoe dye polish, fill it up with the ink we were mixing, and suddenly, you had a completely different type of marker at your disposal.

Finding those old shoe dye applicators is a challenge these days, unless you stumble upon a stash from the 80s or 90s.

Mini and Uni-Wides

While homemade TNT markers were the go-to weapon for early graffiti bombers, a select few retail markers, especially the large, specialized ones designed for sign painters and calligraphists, could still do the job effectively.

For artists with nimble hands and ample pockets, a quick shoplifting trip to the stationery store could yield some professional-grade bombing tools. But using these markers effectively required the right touch.

Some individuals opted for standard markers, such as the Unique pens from art stores. There were also the older Flo-Pens from Flo-Master, which the more seasoned graffiti writers favored.

The standard Pilot marker, available at stationery stores, was another option. Additionally, there were markers known as Mini-wides, featuring a felt tip, which were initially created for calligraphy and were commonly found in art stores. There was also a broader one called the Uni-wide, shaped like an oval, which was a top choice.

If you were serious about your graffiti, you had to possess at least a mini or a uni. However, the catch was that you had to know how to wield them effectively. Interestingly, I learned calligraphy in fourth grade, and I began bombing in fifth or sixth grade, so all that calligraphy knowledge became quite handy when I got my hands on a chiseled square marker for graffiti.

Spray Caps

During the ’70s and early ’80s, custom spray can nozzles with various sizes and widths became essential for graffiti artists to create specific line styles and increase the spray force of their cans.

However, in those early days, the only custom caps available were those swiped from foam and cleaner spray cans found in hardware stores.

In the early days, WD-40 caps were used, but they produced an explosive burst of paint, which wasn’t ideal for graffiti.

There was one company, Jiffy-Foam, that produced various foam sprays, like Kitchen Magic and Cabinet Magic, which had caps designed for a slow and controlled spray.

These caps were larger, making them suitable for Krylon or Rust-Oleum cans, effectively transforming them into fat caps.

However, in the 1980s, with everyone shoplifting, it became increasingly difficult to steal whole cans from hardware stores because the managers and cashiers were always watching.

So, you had to be quick and discreet. You would open the can, grab the spray cap with your teeth, bite it off, keep it in your mouth, and then close the can, making it look like you hadn’t tampered with it.

You’d put it back on the shelf and continue doing this with multiple cans. You could end up with ten caps in your mouth, which felt quite strange but was just how it all started.

The downside of this practice was the inconvenience it caused for people who genuinely needed those cleaning foam cans, only to discover that the spray caps had been removed by graffiti artists.

Keys To the Kingdom

In the era before programmable code-locks, plastic cards with microchips, and facial ID scanners, simple metal keys were the sole means of accessing the most secure zones within the NYC MTA.

For graffiti bombers, possessing a ring full of stolen transit keys could be the difference between success and failure, especially if it included the coveted MTA skeleton key.

Keys were the ultimate ticket; whoever had those keys had the power to get in. Bolt cutters were valuable too, but various keys were the key to success.

These keys allowed access to the train stations, and in some cases, even inside the trains themselves. While perhaps some individuals had connections or family members who could obtain copies, in many cases, you had to resort to theft.

You’d keep an eye out for the MTA personnel and then swiftly snatch their keyring. Some of these keyrings held special skeleton keys that could unlock trains.

If your graffiti mission involved outdoor pieces, you only needed keys to access the overnight exits. However, if you were planning to create art inside a train car, you required the skeleton keys that could open all the locks.

Of course, you still needed that initial key to gain entry, but with those extra keys, you could enter the layups, where the trains parked overnight, open the train doors, and let everyone jump inside.

Some graffiti writers even possessed keys that could start the trains or turn on the heat in the winter, further enhancing their capabilities and the allure of their underground artistry.

Less Lethal Weaponry

Indeed, for both up-and-coming graffiti artists looking to make their mark and seasoned veterans taking a break between larger missions, there were tools of a less impactful nature than TNT bombers and customized spray cans.

These tools might not have the longevity or scale of the heavy hitters, but they offered effective means of artistic expression. Shaving sprays and stickers, with their ease of use and wide accessibility, provided alternative avenues for street art flexes that were both creative and impressive in their own right.

Shaving Cream

I recall how kids would engage in shaving cream pranks on Halloween. Well, we took it to another level by using shaving cream for graffiti, but the stock shaving cream cap wouldn’t do the trick.

What we used to do is insert a twig or a metal pin into the cap, then heat it up with a lighter until it became small and narrow. When you removed the twig, you were left with a slim shaving cream cap that could spray like crazy, reaching up to 20 feet.

This allowed us to create graffiti pieces high up on buildings using shaving cream as our medium.

Stickers

In the 1980s, graffiti artists often used “Hello My Name is…” stickers or large rolls of blank square stickers. These stickers were commonly swiped from stores like Woolworths or any stationery shop. As for post office stickers, particularly the blank Priority Mail labels, they gained popularity in the late ’90s.

Initially, they would just lay them out for people to grab, but so many were being taken that they started keeping them behind the counter.

However, clever graffiti writers soon realized that they could simply contact the post office and request a stack of stickers to be sent to their homes – completely free of charge.

They’d make a call or write a letter saying, “Send me a 100-pack,” and the post office would comply. It was as easy as that.

It seems that old habits die hard. The graffiti writer spirit must have kicked in when you were recently at the post office. You saw stacks of stickers there and couldn’t resist taking some just for the heck of it, despite the change in times.

That graffiti-writer impulse can be hard to shake!

[Spin.com]