The Legendary Shirt Kings

Based in Jamaica, Queens, Shirt Kings became the epicenter of streetwear culture. We spoke with co-founder Mighty Nike about how the brand paved the way for Black-owned streetwear and influenced hip-hop fashion on a national scale.

Building 534 looks like any of the other 27 six-story buildings in Brooklyn’s Marcy Houses. Its reddish-brown brick exterior is familiar, repetitive, and a bit foreboding. Built by the New York City Housing Authority in 1949 and named after former Governor William L. Marcy, this Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood has become a cornerstone of hip-hop lore.

On the first floor of Building 534, facing Flushing Avenue, lived Clyde A. Harewood, aka Mighty Nike, co-founder of the pioneering streetwear label Shirt Kings. From the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, there were only two places a street-savvy youth could get one-of-a-kind clothing: Dapper Dan in Harlem and Shirt Kings’ booth at the Jamaica Colosseum Mall in Queens.

For years, Shirt Kings crafted bespoke pieces loved by hip-hop pioneers, local trendsetters, and everyday fans. Their airbrushed jackets, denim, and sweatshirts — featuring Cuban links, dookie ropes, and bold graphics — defined street style. Founded by King Kasheme, King Phade, and Mighty Nike, Shirt Kings ignited a wave of Black-owned clothing brands, including Walker Wear, Fubu, and Mecca, setting the stage for hip-hop’s fashion influence to reach mainstream brands. Mighty Nike witnessed firsthand how Black street style evolved into a multi-million-dollar industry.

The Rise of Mighty Nike

Despite neighborhood challenges, Harewood’s Marcy Houses block was alive with creativity. His Caribbean immigrant family moved to Brooklyn in the early 1970s, and Clyde spent hours drawing as a child, inspired by cartoons like Mickey Mouse and Betty Boop — but his favorite was Mighty Mouse. He later tattooed a Mighty Mouse image on his arm with “Mighty Nike” underneath. On the fifth floor of the same building lived a younger kid named Shawn Corey Carter.

“It wasn’t easy growing up in Marcy,” Nike recalled. “Kids teased the Caribbean kids sometimes. Marcy Projects had two sides, Flushing and Myrtle Avenues, and we’d go over to the ‘other side’ to see what was happening.”

By their teen years, Brooklyn was a hub for style and music. Clyde hung with a tight crew including Shawn’s brother Eric and rapper Jaz-O, rapping, DJ’ing, and experimenting with the evolving Brooklyn sound. Across New York, hip-hop was spreading through parks, clubs, mixtapes, and graffiti on city trains.

At Manhattan’s High School of Art and Design, Clyde met graffiti artist Edwin “Phade” Sacasa and Queens native Rafael “Kasheme” Avery. The school nurtured a creative force including Daze, Doze, and Lady Pink. Clyde’s art combined iconic characters with street fashion, earning him the nickname Mighty Nike from a friend impressed by his love of cartoons and Nike sneakers.

“All my characters wore Fila or Nike,” Nike said. “I’d customize Nikes and people would ask where I got them. I’d say New Jersey. I became ‘the Nike kid.’”

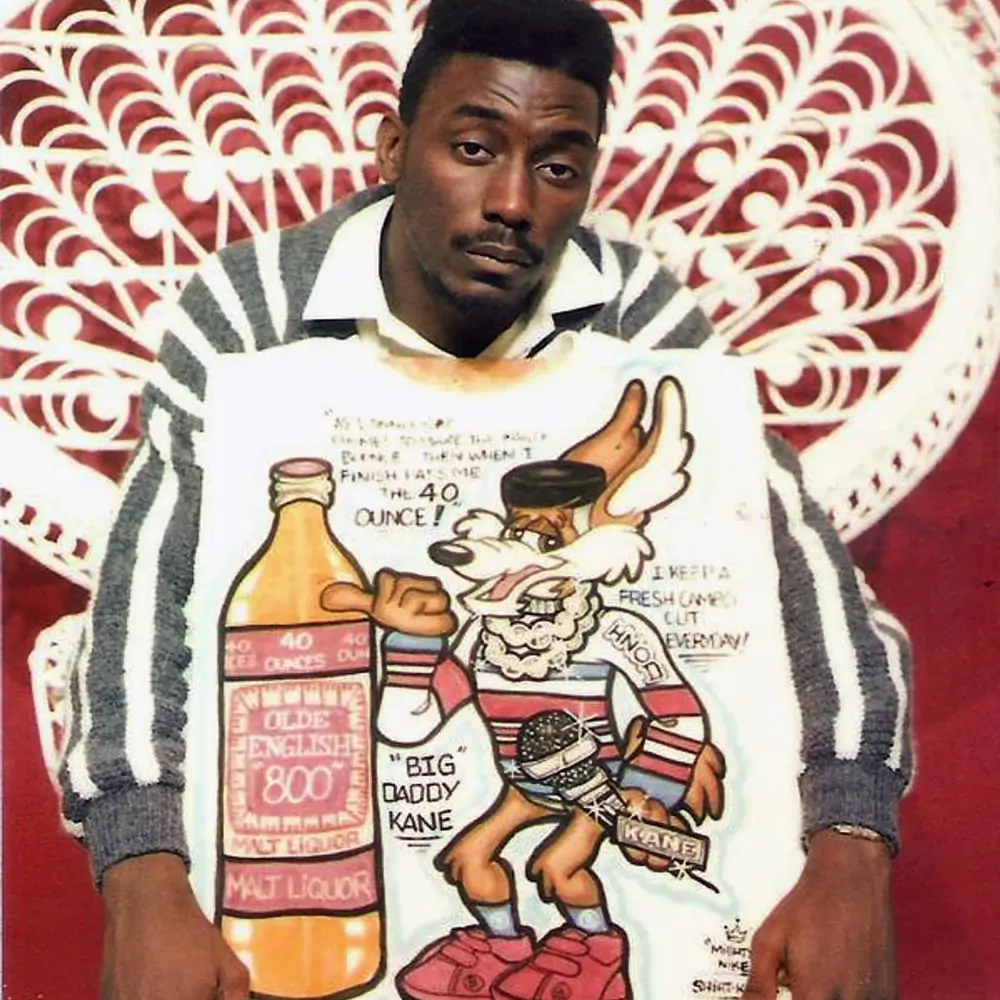

Nike and his crew frequented New York clubs like Funhouse, The Roxy, and Bond’s International, where style was king: Gazelle glasses, suede Pumas, shearling jackets, Kangols, bubble jackets, and gold ropes defined the era. Icons like Big Daddy Kane, Biz Markie, Kool G. Rap, and LL Cool J amplified this street style through album covers and music videos.

Shirt Kings at the Jamaica Colosseum

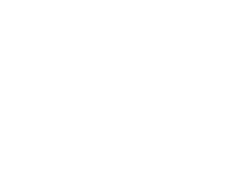

By the mid-1980s, Phade began creating silk-screen shirts with collaborator D Ferg. Nike and Kasheme, laid off from construction, joined the effort, and in 1986, the trio founded Shirt Kings at the Jamaica Colosseum Mall. During the crack era, wealthy kingpins sought customized streetwear to signal status. Their booth, placed strategically next to jewelers, displayed airbrushed designs along the back wall.

“Everybody had money in the ’80s. Fat Cat and the Supreme Team wanted our shirts,” Nike said. “Between us and Dapper Dan, we were the two places to go. We focused on art and airbrush, Dap on logos.”

The booth became a hub for neighborhood youth and hip-hop artists alike. Nike, Phade, and Kasheme collaborated with a team of airbrush artists to meet growing demand. Their hand-painted jackets and sweatshirts featured pop culture icons in hip-hop style, often embellished with rhinestones.

Biz Markie commissioned his first shirt, wearing it in Black Beat magazine, which put Shirt Kings on the map. Soon, Run-DMC, Big Daddy Kane, Salt-N-Pepa, LL Cool J, and other hip-hop legends became clients. Album covers like Audio Two’s “What More Can I Say?” showcased their signature airbrushed look, solidifying Shirt Kings’ influence on hip-hop fashion.

From Streetwear to Corporate Recognition

Shirt Kings’ bespoke approach inspired a wave of Black-owned streetwear brands like Fashion In Effect, Karl Kani, Fubu, and Cross Colours, establishing the foundation for urban fashion’s rise. By the mid-1990s, as hip-hop entered mainstream culture, Shirt Kings faced new challenges. Larger budgets, shifting tastes, and the commercialization of urban fashion made it harder for three friends to maintain their operation.

Shirt Kings closed their Coliseum booth in 1995. Nike and Kasheme continued working locally, while Phade moved to Los Angeles. Kasheme passed away in 2003 at just 38.

Legacy and the Next Chapter

Today, at Murda Ink Tattoo in Hempstead, Long Island, Nike continues to airbrush and draw, blending his art with tattoo work. The shop features his original Shirt Kings creations alongside tattoos, preserving the brand’s legacy.

“I’m always gonna be Shirt Kings,” Nike said. “I’ll never stop painting, airbrushing, or drawing. We created something that forever changed streetwear and how Black fashion entrepreneurs build their brands.”

[via]