The Story Behind The Hard-To-Find Lil Wayne Documentary

“The Carter” stands as an exceptional hip-hop documentary, offering an unfiltered glimpse into the captivating life of Lil Wayne during the pivotal year of 2008. Regrettably, the film encountered challenges in its release, rendering it elusive for eager audiences to discover. Allow us to unravel the tale behind this extraordinary and contentious cinematic creation.

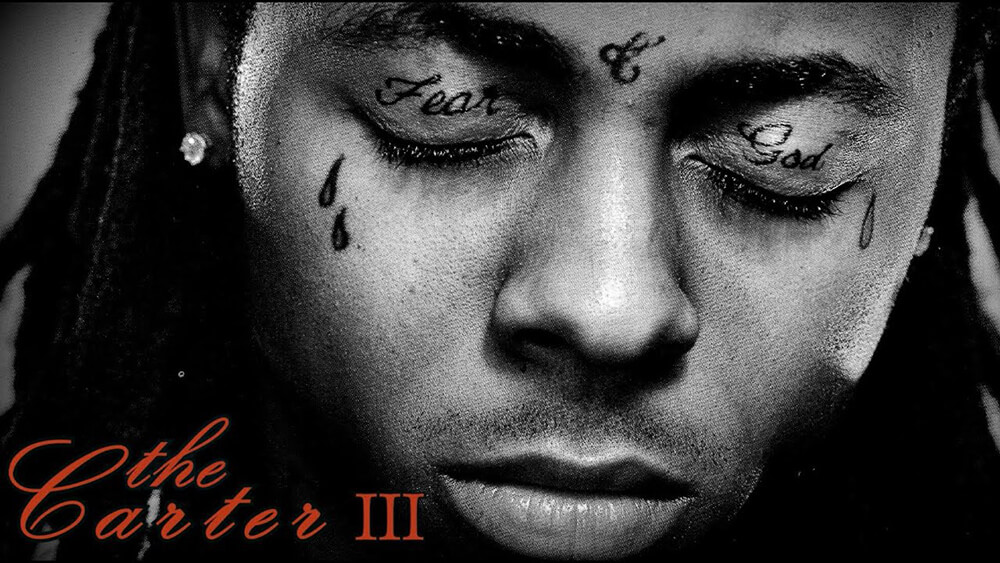

The Carter 3

In the eventful year of 2008, Lil Wayne embarked on a whirlwind journey that saw him traverse the globe, leaving a trail of impromptu studio sessions in his wake. Driven by an unwavering determination, he relentlessly recorded new music wherever he found himself, be it hotel rooms or tour buses. And the fruits of his labor were nothing short of astonishing. When his sixth studio album, “Tha Carter III,” hit the airwaves in June, Lil Wayne’s popularity had soared to unprecedented heights. Despite the album leaking ahead of its official release, it astoundingly sold an astonishing one million copies in its very first week.

At the youthful age of 26, Lil Wayne embraced a rockstar lifestyle, solidifying his position as one of the industry’s preeminent artists. The music he created during this era would leave an indelible mark on the rap landscape, altering its course forever. Often, historic moments such as these slip through the cracks of documentation, residing solely in hushed schoolyard tales and embellished accounts. However, fortune smiled upon us, for cameras were constantly rolling in Lil Wayne’s presence throughout the year. Even more remarkably, the individual behind the lens possessed an unwavering commitment to capturing an unfiltered and genuine portrayal of the artist.

Filmmaker Adam Bhala Lough had grown weary of the polished and contrived nature of many music documentaries, where excessive attention was given to interviews with collaborators and critics, rather than simply unveiling the authentic reality of the musician at the film’s core. Thankfully, Lil Wayne shared Lough’s perspective and yearned for a documentary that captured the raw essence akin to a SMACK DVD. Thus, for a span of nine months, Lough trailed Lil Wayne with his camera, meticulously documenting every facet of his life. From electrifying sold-out concerts to exhausting press junkets and late-night recording sessions in hotel rooms, Lough bore witness to an “intensely creative” environment that mirrored a perpetual 24/7 studio session.

The Documentary

Upon completion of the documentary, Lil Wayne purportedly expressed great satisfaction with the final product. According to a 2009 MTV interview with producer Quincy Jones III, Wayne was described as “ecstatic” about the film. And indeed, there were many reasons for his delight. Titled “The Carter,” the documentary provides a rare and precious window into Wayne’s legendary recording process and his unorthodox perspective on the world.

The film’s most enduring moments capture Wayne in his element, as he unveils a large black bag filled with recording equipment and effortlessly creates music on the spot. With a seamless combination of improvisation and meticulous artistry, he fleshes out some of his most iconic songs before our eyes, showcasing his incomparable talent. In more intimate scenes, we witness Wayne reflecting on his interactions with journalists, displaying his raw authenticity. He bristles at one interviewer’s question regarding his ability to foresee his own demise, responding with disdain, “I don’t foresee shit. I’m not that good. I’m good, not that good. I don’t see my death.” These candid moments, devoid of artifice, contribute to the film’s allure.

What sets “The Carter” apart is its unflinching focus on portraying Wayne’s life during this specific period, eschewing a detached and panoramic viewpoint. Instead, it delves deep into the intensely human aspects of his existence, unraveling the layers of a captivating and idiosyncratic entertainer. By providing an up-close and personal portrayal, the documentary grants viewers a privileged glimpse into the true essence of Lil Wayne during this extraordinary chapter of his journey.

The Lawsuit

As the release of “The Carter” drew near, the situation took a dramatic turn for the worse. Lil Wayne’s team withdrew their support and filed a lawsuit to prevent the film’s distribution. It was reported that they claimed they were promised final editing rights and demanded the removal of certain scenes. However, the lawsuit was eventually dismissed by a judge, and the film was released directly to DVD in November 2009. Despite its limited release, “The Carter” garnered widespread critical acclaim, receiving accolades from esteemed outlets such as The New York Times, The Guardian, Rolling Stone, Huffington Post, and Complex. Nevertheless, the damage had been done, and as time passed, the documentary became incredibly elusive. In the present day, it remains nearly impossible to find, with no official means of purchase or streaming available. One would have to embark on an extensive search on platforms like Vimeo and YouTube to access it.

To this day, director Adam Bhala Lough has not received direct feedback from Lil Wayne regarding his thoughts on the film. However, in an interview with Complex, Lough suggests that some individuals on Wayne’s team may have deemed it too risky to release such an unfiltered documentary, particularly considering Wayne’s heightened popularity. The inclusion of scenes depicting Wayne consuming lean (a controversial substance) may have posed a potential threat to the vast financial stakes and lucrative business opportunities involved.

Nonetheless, “The Carter” will forever be remembered as a groundbreaking music documentary, offering a rare glimpse into the creative process of one of the most influential artists of his generation. Praised by numerous critics as one of the greatest music documentaries of all time, its significance remains undeniable. Lough expresses his hope for a future re-release of the film, but he is currently engaged in other projects. Since “The Carter,” he has worked on documentaries like “The Motivation” and “The Upsetter: The Life & Music of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry,” among others. His upcoming project, a docu-series titled “Telemarketers,” is set to air on HBO on Sunday nights in August, representing his most significant endeavor to date.

In celebration of the 15-year anniversary of “Tha Carter III” and Complex’s ongoing homage to hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, the following is an interview with director Adam Bhala Lough, shedding light on the story behind “The Carter” documentary. The interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

The Interview

When you started making this documentary, what was your goal?

I wanted it to be different and weird and experimental. Initially, I went in with the goal of it being pure cinéma vérité—pretty close to how it ended up, to be honest.

Both Wayne and I, without even having talked to each other about it, were looking to do a documentary that was less of the typical VH1 Behind the Music style, where it’s overly produced and overly written and you can really feel the hand of the company behind it. We both wanted to do something more raw.

In Wayne’s mind, I think he wanted it to be raw, because he was coming at it from a street perspective. He wanted to do more of a SMACK DVD-style raw portrait, and I wanted to do the arthouse version of that. I was trying to capture something that was real and raw and a reflection of who Wayne was, without having a bunch of interviewees sit around and talk about who he was. Basically, I wanted to capture the essence of who he was through the footage, as opposed to dragging out some music critics to talk about him. Certain production constraints and things that Wayne wanted also informed the language of the film. A lot of that was my choice, and a lot of it was Wayne’s choice.

That was the approach from the very beginning, and it’s what we shot, but it almost didn’t happen. The only way that we were able to pull that off was because we got into Sundance. We submitted the film in September, and Sundance was in January. But when it got in, other producers and people associated with the project wanted to change the film. There was a lot of pressure on me to make, for instance, a whole biographical section on Wayne that would’ve been like a traditional PBS-style sequence. They were like, “You can have the raw stuff in it, but you need to constantly be cutting back to illustrate for the audience where he was born, how he was raised, who his parents were, blah, blah, blah. Oh, we need to interview some critics and contemporaries to talk about him.”

“We both wanted the film to be raw. Wayne wanted to do more of a SMACK DVD-style raw portrait, and I wanted to do the arthouse version of that.”

So they were trying to turn the film into the exact kind of traditional documentary that you and Wayne were trying to avoid?

Yeah. So I was basically like, “No, that’s not what I want to do, and that’s not what Wayne wants to do.” We would not have won the battle had we not gotten into Sundance, though. When we got in, Sundance essentially told us, “Well, you got in based on this version, so you can’t go and change and make a whole new version.” So thankfully, we got in and we were able to retain almost the exact cut that we submitted, which was extremely rough, edited in a fury of a few months, which lent itself to what’s so special about the documentary. It wasn’t overworked. It wasn’t overthought. In the metaphor of rap music, it was more like a freestyle off the dome.

Yeah, it’s a style that fits naturally with Wayne’s own musical approach.

Exactly. We both wanted it to be that way, and nobody else did. If we hadn’t gotten into Sundance, the version that would’ve come out would’ve sucked. It would’ve been boring. I mean, I guess it probably would’ve actually come out, since this version didn’t actually get a real release because it was too raw. But on the flip side, this version has an infamous quality that you can’t replicate.

The documentary has a really great fly-on-the-wall feel to it. It’s almost like Wayne didn’t know or care that he was being filmed. How were you able to pull that off?

I had a small crew, but very early on, we realized I couldn’t even have a crew because we were on the bus and in places where only I could really fit. So that informed a lot of what I was able to capture. But in terms of the naturalism of it, I think a big part of that was just Wayne himself, because he had been a star in some capacity since he was a little kid. So he was very accustomed to having cameras around him. He’s very natural with the cameras. At some point, I was there for so long that he started to trust me. And at a point, I think he pretty much forgot I was even there. Filming for hours and hours and hours, you start to get used to each other.

When you entered Wayne’s world for the first time, what did you experience? What was it like? What surprised you?

It was interesting because his world really changed in a big way from the first day I met him, which was in Boston. It was at a radio station concert. One of those shows where he was not a headliner, but he was still famous and still a big deal in the hip-hop community. But then at the end, when we stopped filming, he was pretty much a pop star, rockstar, megastar. So his world really changed quite a bit in those nine months. He was living the life.

You can see some of it in the documentary. The whole business aspect changed. Ultimately, the reason that the film never came out is because of what we’re talking about right now. Had he not become this mainstream star, I think the film would’ve come out. Everything started to change so quickly when he sold a million records. All these things started to line up, and some of the people around him were like, “Oh, we can’t do this. We can’t do that.”

It suddenly became more about money, sponsorship opportunities, commercials, and bigger things that a normal rapper from New Orleans wouldn’t think about or have to deal with. Some of his handlers were getting a lot of advice from lawyers like, “Oh, you can’t do this, you can’t do that. If you want to be on TV or if you want to be this level of star, you have to start to change certain things about the appearance of your client.” Had he stayed at the same level of popularity as he was when we started, I don’t think anyone would’ve had a problem with the movie.

What was it like trying to document someone who was becoming one of the biggest stars in the world?

It got more interesting because he was just doing more stuff constantly. There was more to film. It was like, “Oh, we’re shooting this music video with The Game, and then the next day we’re going to the MTV Music Awards, and then we’re going to this thing, and then at some point we have to squeeze in studio time to record this thing with T-Pain.” It was just constant action, so that was a good thing. That was fun.

In the beginning of the documentary, you write, “We have done our best to reveal intimate details of his life through his music and lyrics, lyrics that we believe reveal more about his life than what he revealed to us during our nearly 6 months of filming him.” Why did you make that choice to use his own music as the primary way of telling the story?

That was definitely a specific choice. We tried to pull certain moments from certain songs that were biographical or helped explain how he felt about certain things like. Like the song we used about syrup [codeine]… Through his lyrics, he was revealing who he was far more effectively and interestingly than if he was just saying it in an interview.

There’s the lyric from the Playaz Circle album in the movie where he talks about how sizzurp is going to kill him. He’s saying it in a sort of joking, offhanded way, almost mocking, but there’s maybe some underlying anxiety there that part of him believes. To me, that speaks volumes about who he is. That’s why I specifically pulled lyrics like those. In my mind, that’s far more effective than if we just interviewed him and had him talk about it.

In the doc, Wayne would often pull out his little mobile recording kit and make music wherever he was. Is that how it was 24/7?

Yeah, that was mainly what we were capturing. It seemed to me that he was making probably a song a day, if not more. At least one song he would do, so it wasn’t hard to capture that.

He spent a lot of his time listening back to his own music, too, right?

Yeah, I wondered if he was doing that because he was tweaking it, because he would tweak it later. I never asked him, but I don’t know if he was doing that because he was listening specifically for mistakes or words he wanted to change, or if he just liked to listen to himself.

Maybe a mix of both.

Yeah, maybe both. I know Kanye does the same thing. He’s constantly changing lyrics and stuff.

There’s a disclaimer at the beginning of the film that says Wayne didn’t want to do any formal interviews. When he told you that, what was your response? And how did you maneuver around that?

The disclaimer was put at the beginning of the film by the lawyers. I didn’t write it and it had nothing to do with me or my process. It was something that was just sort of slapped on there right before Sundance.

There are several clips of Wayne talking while being interviewed. How did you get those clips? Did you just film him while he was doing press with other journalists?

He ended up going to a press junket in Amsterdam. As he started getting huge, the European press wanted to interview him, so Cortez Bryant did something very smart. Instead of having Wayne go do all these interviews, he basically was like, “We’ll set up a junket in Amsterdam because Wayne loves to smoke weed, so we’ll go to Amsterdam, we’ll set up a junket, and then all the journalists will just come to him.” That’s how it happened. We were just filming behind the scenes of that particular junket.

I know the doc was filmed across a nine-month period or so. Were you with him every day for that period? Or were you popping in and out?

I was popping in and out. There were times when I would show up and he wouldn’t want to shoot. So I’d be sitting in a hotel room for three days waiting, and then he’d finally say he wanted to shoot. Once we got in and I was able to start shooting with him, then I wouldn’t leave. So I would just have granola bars on me and I would be constantly shooting, because once I was there, he would never ask me to leave.

What he did for me that he probably doesn’t even realize is that he made me gain this really zen attitude for all my future films, and life in general. Like, I have no control over this guy, so I have to just be totally zen about it. When he says he wants to film, we’ll film, and it’s all about relinquishing control completely to him. In a weird way, that helped me with all the future films that I made.

What were the challenges of documenting that time in Wayne’s life as a filmmaker? What were the obstacles?

Just getting to actually start rolling camera. The stars had to align. He had to be mentally ready to start filming, and I had to be available. My first child was born right during filming, so I was constantly going back and forth to be with my daughter in Brooklyn. In the end, I think he appreciated that I wasn’t in his face all the time, but there were times where his handlers would be like, “What? You can’t come film this? He wants you to film this.” But I had to be with my daughter. The great irony of documentary filmmaking, though, is the events that everybody thinks are so important often end up on the cutting room floor and it’s the mundane moments you never expect that end up being the most memorable scenes in the film.

“Meek Mill recently told me, ‘When I was a little kid first rapping, I watched that movie every single day. That was my guide.’ I hope it continues to inspire artists to do creative shit.”

One of my favorite scenes is when you visit his daughter. Why was it important to you to include that scene?

That was definitely inspired by the fact that my daughter was just born. I think it was more of a personal thing, but it ended up being a good interview and people liked it. I hate using this word, but I guess it humanized him in a certain way, especially to those people who were haters or naysayers. Back in the day, people would come up to me and get angry at me, like, “Why did you make a whole documentary about that guy when you could have made it on somebody more important?” They didn’t realize or understand that he’s a genius and one of the greatest American artists of his generation. Now everybody’s starting to catch up, but I got a lot of hate and a lot of shitty comments from film critics and people in the film world.

A lot of the conversation around the documentary ended up being about Wayne’s use of lean. When you did interviews for the film after it came out, that’s all anyone wanted to ask about. A decade later, how do you feel about that discourse that followed the film?

The reason I included the lean discussion in the film was because it was something new to me that I didn’t really know much about, so I thought it was interesting. It was a new thing that was unexplored and not understood very well. So I don’t blame the writers for wanting to ask about it. But I think there was a certain click-baity headline that would be written by these people about this weirdo rapper who drinks sizzurp and is a drug addict. There’s a click-baity aspect to it that they sort of clung onto. That disappoints me obviously, because there’s so many more interesting things about the film and about him. But like I said, in some ways I’m like, “Well, I included it in the film, so anything’s fair game.”

You said your whole goal was to capture the raw reality of his life and career, so it probably seemed necessary to include this, since it was a big part of his life at the time?

Well, the first time that he pulled out the prescription bottle in front of me when I was filming, I was shocked. I really didn’t think he was going to do that. I thought he was going to hide it from me. I remember saying something to him about it, like, “Do you want me to put the camera away?” And he’s just like, “Nah, fuck it.”

So to me, I felt like it was fair game to use it and that he wouldn’t care. Because at that moment, I gave him the opportunity to be like, “Yeah, put the camera away. Don’t film this.” And he didn’t say that. He was like, “Nah, go ahead.” So for me, I thought it was fair game. Part of me still thinks he feels that way, too. But as I was saying earlier, he got so famous that his handlers and people around him were like, “Dude, you can’t be associated with this anymore because it’s too dark.” So they got in his ear.

He didn’t seem to care prior to that. There were videos that had been sitting on YouTube for years where he was explaining to the camera how to mix sizzurp. But he just got so big that the lawyers and handlers around him were like, “Hey, ESPN is not going to fucking put you on TV if you’re associated with this shit. We’ve got to cut it out.” I don’t know how he feels about that—I wish I could have asked him—but I still think he thinks that’s bullshit, and he would ultimately not care that those scenes were in the film. I think he’s like, “Whatever, that’s me. That’s what I was doing at the time. I didn’t protest to the camera being there, so fuck it.”

But when you become that famous, it’s like you’re no longer really a person. It’s like you’re a giant corporation with all these fucking tentacles and all these people trying to control things for you. You don’t control your image and how it’s filtered and where it ends up. So that’s what happened, ultimately. That’s why the film was banned, for lack of a better word.

Have you spoken with Wayne or his team since then?

If you watch my skateboarding film, The Motivation, he’s in it right at the very end. I was actually able to make that film because of The Carter. Rob Dyrdek saw The Carter and was a huge fan, so he let me come film Street League and Wayne was just in the stands watching the championship. We didn’t really get to have a real conversation, but you can see he’s in the film and that was the last time I saw him. I kept in touch with Cortez Bryant and I do talk to him every now and then. What Cortez told me was that Wayne and all of them felt like I was doing my job. I was trying to make a really good documentary, and they understood and all was forgiven.

There were deeper things that were going on in terms of money and I wasn’t brought into any of those conversations. I think there were power struggles over the film. I remember at one point Quincy telling me, “Baby’s going to buy the movie for like $1 million and then he’s going to change it and do whatever he wants to it.” For some reason, that never ended up happening, but I had a feeling there were these power struggles going on over the film that I didn’t know about.

I always told Cortez this: “One day you guys are going to thank me because I documented a really extraordinary time in your lives, and nobody else has that. I documented it. One day you guys are going to thank me, and one day you’re going to love the movie.” I know Cortez likes it more and more as the years have passed, but I’d be really curious to hear what Wayne thinks of it as the years pass.

So many documentaries come out that bite the whole style and content of The Carter. And all these really shitty documentaries come out about rappers and other musicians that are just absolutely dreadful and nobody even wants to watch them. But I feel like Wayne got something really special, and maybe it wasn’t what he was expecting. Or maybe it was. Who knows? Maybe The Carter was exactly what Wayne was expecting and what he wanted. It’s just that he got too big and his people were like, “This isn’t a good look for us.”

The film ends with Wayne’s song “DontGetIt” about being misunderstood, while you show a tight shot of the “misunderstood” tattoo on his face. Why did you want to end the film that way?

There were people who failed to understand or even want to understand who Lil Wayne was at the time, for various reasons. I think rap music had a different perception back then, and I think there’s also clearly racism involved. So that’s what that was directed at. But I also think there’s an ironic sort of funny joke underneath it. Like, this is the end of the documentary, and as a documentary filmmaker, I still don’t understand who this dude is.

The tattoo is really amazing, too. The fact that somebody would tattoo the word “misunderstood” on their face is just fascinating. That’s amazing. I never got to ask him that, but I guess he wouldn’t answer either if you asked him. Or he’d have some canned response, but wouldn’t tell you really why. Maybe it’s in his lyrics somewhere. Maybe it’s in that song.

Looking back, how would you describe the overall experience of being around Wayne during that year?

It was an incredible experience that I’m very grateful for. It was fun. It was intensely creative. I can see why that lifestyle is so attractive, especially to other creative people. It’s like a 24/7 studio session almost. It’s nonstop. Like, “We are just going to create nonstop, and we are not going to have to think about life or responsibilities or obligations or bills or even where we’re going to eat next. We’re going to smoke weed and just be creative nonstop.” It’s a very addictive lifestyle and I can see why people get swept up in it. But it’s also not very conducive to being a father or a husband or a son even.

It’s easy to get lost in that world, so in some ways I’m grateful that I was able to move on and do different things with my life, because I can see how a creative person would really burn out from that. But when you’re in it, it’s like entering a whole other world. I’m very grateful I experienced it, too. I was able to spend the better part of a year doing that while I was still young. I was 27, so it was easier for me to hang. Now I don’t think I could put in those crazy hours. I’m too old.

What do you hope is the enduring legacy of the film? How do you hope it’s remembered?

On a purely egotistical level, I would love for the film to be re-released by Criterion Collection. I would love for it to get the positive critical response that is due, and I would love for people to acknowledge how many films after it have just completely ripped it off.

On a deeper level, I don’t care. This film is where I learned about taking a zen attitude in the edit room. There are moments that got put on the cutting room floor that are absolutely incredible and no one will ever get to see them. But it’s okay because I experienced it and that’s what it was there for. And on some level, I hope it inspires artists, which I know that it has.

I was on the phone with Meek Mill the other day about doing a project and he didn’t even know I directed The Carter. But when he found out, he was like, “Really? You directed that movie?” He’s like, “When I was a little kid first rapping, I watched that movie every single day. That was my guide.” So it would be nice if it continues to inspire artists to do creative shit.

How did The Carter affect the rest of your career? What have you been working on since? then?

The Carter completely moved my career into documentary filmmaking, because before that, I was working with actors. I was making narrative projects. I was selling screenplays. I sold a bunch of screenplays to Hollywood. I got into WGA, which I’m still in, on strike right now. But after that came out, I started getting calls about making other documentaries and I just never really looked back.

I have a doc series that’s coming out on HBO that I directed and Josh and Benny Safdie produced. It’s called Telemarketers and it’s coming out on HBO on Sunday nights in August. It’s a limited doc series and it’s by far the biggest thing I’ve ever done. I’m excited about it. That’s basically what I’ve been up to for the past three years.

If people liked The Carter and want to see more of your work, what else should they watch?

The Upsetter is on Criterion Collection’s streaming network, and we also just released a really special director’s cut blu-ray with a little indie label called Factory 25. If you’re a fan of The Carter, you’ll dig that for sure.

[via…]