Social Media Surveillance By the U.S. Government

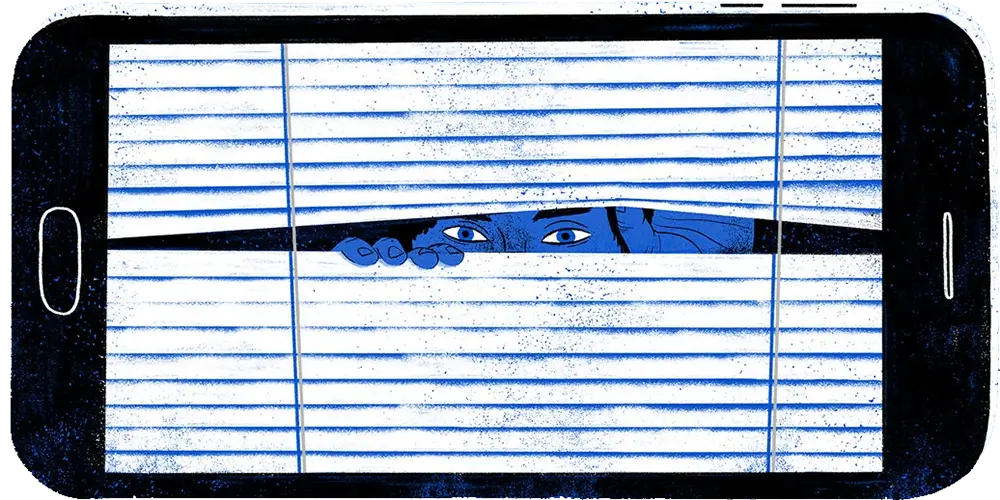

Social Media Surveillance By the U.S. Government has become a significant source of information for U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies for purposes ranging from conducting investigations to screening travelers. This raises a host of civil rights and civil liberties concerns. Someone’s social media presence can reveal an astounding amount of personal information: beliefs, professional and personal networks, health conditions, sexuality, and more.

With that in mind, this growing — and largely unregulated — use of social media by the government is rife with risks for freedom of speech, assembly, and religion, particularly for Black, Latino, and Muslim communities, who are already targeted the most by law enforcement and intelligence efforts. Many of the agencies currently conducting social media surveillance today have a history of using this and other types of monitoring to target minorities and social movements.

Which federal agencies use social media monitoring?

Many federal agencies use social media, including the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Department of State (State Department), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), U.S. Postal Service (USPS), Internal Revenue Service (IRS), U.S. Marshals Service, and Social Security Administration (SSA).

Why do federal agencies monitor social media?

Publicly available information shows that federal agencies use social media for four main — and sometimes overlapping — purposes. The examples below are illustrative and do not capture the full spectrum of social media surveillance by federal agencies.

Investigations: Law enforcement agencies, such as the FBI and some components of DHS, use social media monitoring to assist with criminal and civil investigations. Some of these investigations may not even require a showing of criminal activity. For example, FBI agents can open an “assessment” simply on the basis of an “authorized purpose,” such as preventing crime or terrorism, and without a factual basis.

During assessments, FBI agents can carry out searches of publicly available online information. Subsequent investigative stages, which require some factual basis, open the door for more invasive surveillance tactics, such as the monitoring and recording of chats, direct messages, and other private online communications in real time.

At DHS, Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) — which is part of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) — is the Department’s “principal investigative arm.” HSI asserts in its training materials that it has the authority to enforce any federal law, and relies on social media when conducting investigations on matters ranging from civil immigration violations to terrorism.

ICE agents can look at publicly available social media content for purposes ranging from finding fugitives to gathering evidence in support of investigations to probing “potential criminal activity,” a “threat detection” function discussed below. Agents can also operate undercover online and monitor private online communications, but the circumstances under which they are permitted to do so are not publicly known.

Monitoring to detect threats: Even without opening an assessment or other investigation, FBI agents can monitor public social media postings. DHS components from ICE to its intelligence arm, the Office of Intelligence & Analysis, also monitor social media — including specific individuals — with the goal of identifying potential threats of violence or terrorism.

In addition, the FBI and DHS both engage private companies to conduct online monitoring of this type on their behalf. One firm, for example, was awarded a contract with the FBI in December 2020 to scour social media to proactively identify “national security and public safety-related events” — including various unspecified threats, as well as crimes — which have not yet been reported to law enforcement.

Situational awareness: Social media may provide an “ear to the ground” to help the federal government coordinate a response to breaking events. For example, a range of DHS components — from Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to the National Operations Center (NOC) to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) — monitor the internet, including by keeping tabs on a broad list of websites and keywords being discussed on social media platforms and tracking information from sources like news services and local government agencies.

Privacy impact assessments suggest there are few limits on the content that can be reviewed — for instance, the PIAs list a sweeping range of keywords that are monitored (ranging, for example, from “attack,” “public health,” and “power outage,” to “jihad”). The purposes of such monitoring include helping keep the public, private sector, and governmental partners informed about developments during a crisis such as a natural disaster or terrorist attack; identifying people needing help during an emergency; and knowing about “threats or dangers” to DHS facilities.

“Situational awareness” and “threat detection” overlap because they both involve broad monitoring of social media, but situational awareness has a wider focus and is generally not intended to monitor or preemptively identify specific people who are thought to pose a threat.

Immigration and travel screening: Social media is used to screen and vet travelers and immigrants coming into the United States and even to monitor them while they live here. People applying for a range of immigration benefits also undergo social media checks to verify information in their application and determine whether they pose a security risk.

How can the government’s use of social media harm people?

Government monitoring of social media can work to people’s detriment in at least four ways: (1) wrongly implicating an individual or group in criminal behavior based on their activity on social media; (2) misinterpreting the meaning of social media activity, sometimes with severe consequences; (3) suppressing people’s willingness to talk or connect openly online; and (4) invading individuals’ privacy. These are explained in further detail below.

Assumed criminality: The government may use information from social media to label an individual or group as a threat, including characterizing ordinary activity (like wearing a particular sneaker brand or making common hand signs) or social media connections as evidence of criminal or threatening behavior.

This kind of assumption can have high-stakes consequences. For example, the NYPD wrongly arrested 19-year-old Jelani Henry for attempted murder, after which he was denied bail and jailed for over a year and a half, in large part because prosecutors thought his “likes” and photos on social media proved he was a member of a violent gang.

In another case of guilt by association, DHS officials barred a Palestinian student arriving to study at Harvard from entering the country based on the content of his friends’ social media posts. The student had neither written nor engaged with the posts, which were critical of the U.S. government.

Black, Latino, and Muslim people are especially vulnerable to being falsely labeled threats based on social media activity, given that it is used to inform government decisions that are often already tainted by bias such as gang determinations and travel screening decisions.

Mistaken judgments: It can be difficult to accurately interpret online activity, and the repercussions can be severe. In 2020, police in Wichita, Kansas arrested a teenager on suspicion of inciting a riot based on a mistaken interpretation of his Snapchat post, in which he was actually denouncing violence.

British travelers were interrogated at Los Angeles International Airport and sent back to the U.K. due to a border agent’s misinterpretation of a joking tweet. And DHS and the FBI disseminated reports to a Maine-area intelligence-sharing hub warning of potential violence at anti-police brutality demonstrations based on fake social media posts by right-wing provocateurs, which were distributed as a warning to local police.

Loss of privacy: A person’s social media presence — their posts, comments, photos, likes, group memberships, and so on — can collectively reveal their ethnicity, political views, religious practices, gender identity, sexual orientation, personality traits, and vices. Further, social media can reveal more about a person than they intend.

Platforms’ privacy settings frequently change and can be difficult to navigate, and even when individuals keep information private it can be disclosed through the activity or identity of their connections on social media.

DHS at least has recognized this risk, categorizing social media handles as “sensitive personally identifiable information” that could “result in substantial harm, embarrassment, inconvenience, or unfairness to an individual.” Yet the agency has failed to place robust safeguards on social media monitoring.

Do any laws limit the U.S. government’s activity in this space?

Yes. Surveillance is clearly unconstitutional when a person is specifically targeted for the exercise of rights protected by the First Amendment or on the basis of a characteristic protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, such as race or ethnicity. Social media monitoring may also violate the First Amendment when it burdens constitutionally protected activity without contributing to a legitimate government objective.

Additionally, the Fourth Amendment protects people from “unreasonable searches and seizures” by the government, including searches of data in which people have a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” Social media posts are public, but courts are increasingly recognizing that when the government can collect far more information at a much lower cost than traditional surveillance, the Fourth Amendment may protect that data.

The most notable statutory limit is the Privacy Act, which limits the collection, storage, and sharing of personally identifiable information about U.S. citizens and permanent residents, including social media data. While it bars maintaining records that describe the exercise of a person’s First Amendment rights, the statute contains an exception for such records “within the scope of an authorized law enforcement activity.”

Do the social media platforms have a say in all this?

Social media platforms can and do set rules that limit the government’s ability to conduct surveillance on their users. Facebook’s terms of service require users to identify themselves by their “real names,” with no exception for law enforcement.

After the ACLU exposed that social media monitoring companies were pitching their services to law enforcement agencies as a way to monitor protestors against racial injustice, Twitter and Facebook/Instagram changed or clarified their rules to prohibit the use of their data for surveillance.

That’s not to say the government always plays by the rules: for instance, the FBI and other federal law enforcement agencies permit their agents to use false identities, and the enforcement of most platform rules tends to be murky.

* * *

You can check out this post to download Tor Browser, which is easy to use and completely anonymous. Remember to try and watch what you post on these platforms, Facebook especially because there’s alot of clowns that like to report your posts & images…Facebook is the worst. Anyway, be safe.